The time to resume our Valeant journey has finally come.

I hope everybody had time to digest the first episode. We’re going to carry on from where we left off without much of a transition. For those that are just joining us, you should start here: http://azvalue.blogspot.com.es/2015/08/valeant-detailed-look-inside-dangerous.html?m=1

It seems as if nowadays a very dangerous trend going on in the market involves a bunch of companies that are riding fantastic waves of constant upward moving valuation (over-valuation really).

It has now reached the stage where the smallest hint of a word of caution gets quickly laughed off as naïve and unsophisticated by those who have enjoyed the current ride so much that any notion of there being a different direction than UP sounds foreign to them. How quickly we forget.

Chief among those companies, in my humble opinion, is our friend Valeant.

Valeant has accomplished that by weaving an ingenious web of very elaborate stories about their business that has propelled them to the very top as the most valuable company on the TSX.

Valeant has accomplished that by weaving an ingenious web of very elaborate stories about their business that has propelled them to the very top as the most valuable company on the TSX.

The rise has been so phenomenal that Valeant has even left the Canadian banking giants in the dust. Even though those companies have the state sanctioned oligopoly that is the Canadian financial industry on lockdown. It’s been pretty incredible to witness I must say.

Our goal for the rest of the journey will be to take on all those stories one by one.

However I have decided to rework the outline I gave you in our first installment to make the length more manageable and also since people might want to debate each of these topics individually, I think it’s better to keep them separate. So here’s our new outline for the rest of the journey.

Alright, let’s talk returns on investment.

Let me preface our discussion by saying that among the many fallacies that anchor the Valeant story, there are some that are technical and complicated enough to understandably warrant the confusion that they generate, and trust me, I am as confused as everybody else most of the time, if not more.

However, for two of them, I frankly have a hard time understanding how and why they get away with them. One of them is the Durability Fallacy that we’ll discuss in Part VI and the other is the IRR Fallacy that we’re about to tackle right now.

Our goal for the rest of the journey will be to take on all those stories one by one.

However I have decided to rework the outline I gave you in our first installment to make the length more manageable and also since people might want to debate each of these topics individually, I think it’s better to keep them separate. So here’s our new outline for the rest of the journey.

My goal will remain to try and keep everything informative but hopefully entertaining as well.

- PART IV: The IRR Fallacy and the Stuff Crooks Are Made Of

- PART V: The Cash Earnings Fallacy

- PART VI: The Durability Fallacy, Medicis Case Study and the Synergy Conundrum

- PART VII: Murky Accounting and the Buffett Cockroach Principle + Delusion of Grandeur and The Expert Fallacy

- PART VIII: Unsolicited Advice and Conclusion

Alright, let’s talk returns on investment.

The IRR Fallacy

Let me preface our discussion by saying that among the many fallacies that anchor the Valeant story, there are some that are technical and complicated enough to understandably warrant the confusion that they generate, and trust me, I am as confused as everybody else most of the time, if not more.

However, for two of them, I frankly have a hard time understanding how and why they get away with them. One of them is the Durability Fallacy that we’ll discuss in Part VI and the other is the IRR Fallacy that we’re about to tackle right now.

As we all know by now, Valeant acquires a lot of stuff, a whole lot of stuff.

It's wonderful to keep growing by acquisitions but at the end of the day those acquisitions need to perform otherwise all you're doing is building a big house of cards especially if you’re acquiring nearly all of them using borrowed money.

For many years now, any discussion about the returns that their acquisitions are generating has boiled down to a very simple story. All that story does is describe something they call their Deal Model that they use in deciding what acquisitions to make.

Let me show you a summary of what that Deal Model looks like:

For many years now, any discussion about the returns that their acquisitions are generating has boiled down to a very simple story. All that story does is describe something they call their Deal Model that they use in deciding what acquisitions to make.

Let me show you a summary of what that Deal Model looks like:

This was taken from an investor day presentation given in June 2012 but if you prefer full sentences instead of bullet points, here’s Mr. Schiller's commentary on that particular slide :

“We do rigorous financial modeling. We're looking for 20 percent plus returns at statutory tax rates. We're targeting cash payback periods in the six-year range. Very important, we're not relying on 15-year models with a whole bunch of the value and the terminal value to get our returns. If we’re not going to get our money back quickly, we're not going to make the investment. And lastly, there's been a lot of questions about how we think about acquisition and restructuring costs. They are squarely in the model, we think of them as additional purchase price. So, if we pay $100 for a business and it costs $10 to restructure it, the purchase price is $110. We need to get a return on $110 in order to justify that investment.”

None of this looks particularly remarkable of course, just your typical run of the mill statement by corporate managers everywhere. We read statements like these all the time when going over management presentations.

There is, however, something very particular about this Valeant Deal Model story; in fact, so particular that to make sense of it I decided to coin a new term, or concept, to describe it.

I call it “Doing the Valeant” or simply #DoTheValeant.

Doing the Valeant is a very simple concept, it only requires 3 steps:

- Write a statement on a PowerPoint slide

- Point at the slide and declare “It is true because it is written there!”

and finally the most important step, - Make sure you diligently repeat it over and over again, and before you know it, it will become a reality.

The remarkable thing about those bullet points on that slide I just showed you about Valeant's Deal Model is that that's all there is. Once you've seen that slide and read the commentary that went with it, you've essentially seen almost all there is to see about their Deal Model. You would be hard pressed to find them ever providing any numbers to back their claims up. They just say it.

The kicker, however, is that they've said it, and repeated it, so much and for so long that this IRR story has literally taken on a life of its own.

I am confident that if you were to talk to a Valeant shareholder and just started talking about IRRs, they would, without missing a beat, start telling you how Valeant achieves IRRs of 20-30% on all the deals they do. You are not likely, however, to be provided with any numbers that prove out those claims for the simple reason that Valeant themselves don't provide any numbers. (We will do our own IRR calculations later on)

Let me show you Valeant's idea of providing proof. They of course do it in a very Valeant fashion, or I should say, in a #DoTheValeant fashion.

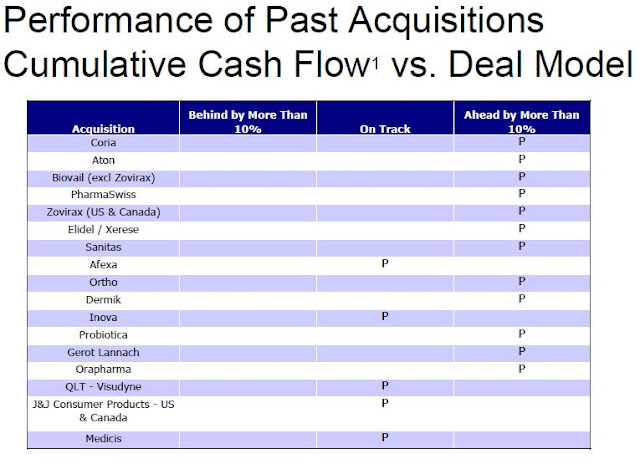

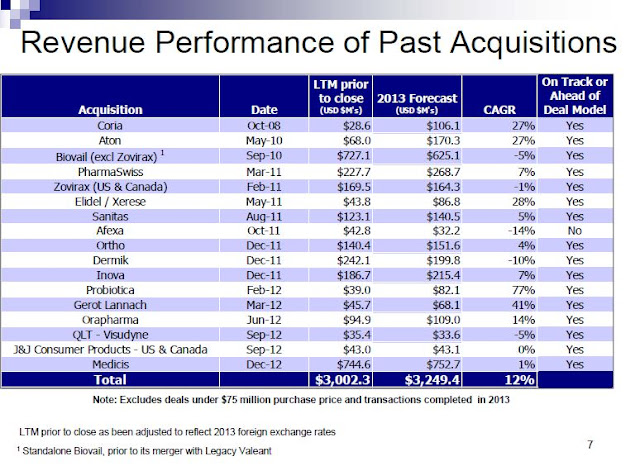

I'm sure you all remember these tables from our previous episode:

Q3 2011 Earnings Presentation:

Q3 2012 Earnings Presentation:

Q2 2013 Earnings Presentation:

I won't make you go through these in detail again as we've already dealt with them.

I'll only point out the first manifestation of what I'm calling #DoTheValeant type of proof. If you look at the 2012 and 2013 tables, you'll see that the far right column supposedly tells us whether or not a particular acquisition is on track/ahead of the Deal Model, or not. Why, or how, is it that they are on track? I'm not sure. Because it is written there I guess.

Of course the tables above were just about top line revenue performance, and calculating an IRR has to do with cash flows delivered by those assets not just revenue.

Well, not to worry because those slides were followed by another set of slides supposed to show us how the cash flows from those assets are delivering on their Deal Model.

2011:

2012

2013:

Tables like these always puzzle me to tell you the truth because even though they’re titled “Performance of Past Acquisition Cash Flow vs. Deal Model”, I find them to essentially provide no value at all.

Let’s take the 2012 one for example, here’s what Mr. Pearson was saying about it on the conference call:

Here’s a genuine question for everybody, what would your answer be if I was to pick one of those acquisitions, say Pharmaswiss, and then asked you: Based on the table above can you show me how it is delivering on that Deal Model that promises an IRR of at least 20%?

“Turning to the next metric, cash flows. Just to remind everyone, we target a 20% plus internal rate of return using statutory tax rates on all our deals. Let us now turn to the cash flows generated by the acquisitions we have made. These cash flows are clearly the most important value driver and the best measure of a deal's success. We are pleased to report that over 90% of the acquisitions made since 2008 are ahead of the deal model from a cash generation standpoint. In the aggregate, we are substantially ahead of the forecasted cash flows we expected to deliver.”Here’s the sentence that puzzles me the most in that paragraph:

“These cash flows are clearly the most important value driver and the best measure of a deal’s success.”These cash flows? What cash flows? All I see are check marks in a table.

Here’s a genuine question for everybody, what would your answer be if I was to pick one of those acquisitions, say Pharmaswiss, and then asked you: Based on the table above can you show me how it is delivering on that Deal Model that promises an IRR of at least 20%?

This, in a nutshell, is the essence of the #DoTheValeant technique because your answer can only be: “It must be true because Valeant says so”.

In fact, let me show you what my version of that 2012 (or any year for that matter) table looks like:

By the way, before you go ahead and start comparing and contrasting them, let me save you some time by telling you that there is absolutely no rhyme or reason to my version. Absolutely none. I just put random checkmarks in there. I would however like to see how anybody would go about disproving mine versus Valeant’s version. To do so you would have to answer a few questions:

- Do you know what that “Deal Model” looks like? Has anyone ever seen it? Or even tried to reconstruct it?

- How can you prove me wrong if they never provide numbers for us to decide whether a 20% IRR has been achieved

Alright folks, we'll mark a short break here because I feel like I have to alert everyone that now is one of those moments where I should ask you all to pay particular attention because the following few paragraphs are, in my opinion, among the most important in this entire Valeant journey.

Let me confess a little white lie first. When I said that Valeant has never provided cash flow numbers for those deals to prove their claims that nearly everything they acquire generates a 20% IRR, it wasn't totally true because they did.

It happened once and it was gone very quickly, if you blinked, you probably missed it.

In Q3 2012, those two tables (the revenue one and the check marks one) were followed by another one.

This one:

You see, a table like this one, to me, is akin to a boxer lowering his guard and exposing his chin. Let us see why.

Everyone can immediately see that the 3rd column, “Cash Generated since Close", is giving us exactly what we've been looking for.

Valeant is finally providing actual cash flow numbers as opposed to just putting a check mark in a box. This one column, on this one slide is really all one needs to get a clearer picture of what kind of company we’re dealing with in Valeant.

This slide is particularly interesting because it is supposed to be providing proof for their cash payback period of 5 to 6 years claims so one would think that those numbers are exactly what we’re told they are, i.e. actual cash generated to date beginning with the closing date of each one of those deals.

If you've been with us since the beginning, there’s a name that should immediately stand out on that list.

Our good friend Sanitas is back.

First a quick summary of what we have here:

First a quick summary of what we have here:

- The Sanitas acquisition was closed in August 2011 so we're given a cash generated number from August 2011 through 9/30/2012.

- So according to Valeant, Sanitas’ operations generated $99M in cash between Q3 2011 and Q3 2012.

I will stick to that principle until the very end of our journey in the hope that I won’t see a #DoTheAZValue hashtag get started on Twitter accusing me of making stuff up.

So with that in mind, we’re about to take a look at Sanitas' financials and like I said in our first installment, those financials are public and audited. So if you have access to tools like FactSet, Bloomberg terminals, CapitalIQ etc. you can log into your account and access them.

So with that in mind, we’re about to take a look at Sanitas' financials and like I said in our first installment, those financials are public and audited. So if you have access to tools like FactSet, Bloomberg terminals, CapitalIQ etc. you can log into your account and access them.

In fact, I would invite to do so right now.

My own numbers were downloaded from CapitalIQ so if you’re using a different tool they might differ slightly due to exchange rates or rounding. But those differences shouldn't be material.

For those who don’t have access to any of these tools, here are Sanitas’ financials for the Q3 2011 though Q3 2012 period that we’re dealing with: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1fSufA7coYJ-4V-X4j4kf9FVnVxZPUk8Lff9QYTA2XBQ/edit?usp=sharing

Alright, now that practicalities are out of the way, first thing we’ll do is go straight to the cash flow statement and take a look at the cash generated by Sanitas’ operations over that period and see if we can come close to Valeant's number and even if there’s a difference, hopefully it won’t be so big that we’re unable to reconcile the two.

For those who don’t have access to any of these tools, here are Sanitas’ financials for the Q3 2011 though Q3 2012 period that we’re dealing with: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1fSufA7coYJ-4V-X4j4kf9FVnVxZPUk8Lff9QYTA2XBQ/edit?usp=sharing

Alright, now that practicalities are out of the way, first thing we’ll do is go straight to the cash flow statement and take a look at the cash generated by Sanitas’ operations over that period and see if we can come close to Valeant's number and even if there’s a difference, hopefully it won’t be so big that we’re unable to reconcile the two.

I won’t even try to be technical about it and argue that one should subtract CAPEX charges to get a free cash flow number or anything of the sort.

Here is Sanitas’ CFFO for that period:

That says $15 million folks. Nowhere near the $99M being claimed by Valeant.

Before we go on to discuss what those two numbers, $15M vs. $99M, actually mean in our quest of understanding Valeant; let me say right away as categorically as I possibly can that the $99M claimed by Valeant is a lie.

It really doesn’t matter what kind of accounting gymnastics one engages in to try and reconcile them, Sanitas simply did not generate $99M in cash between Q3 2011 and Q3 2012.

Before we go on to discuss what those two numbers, $15M vs. $99M, actually mean in our quest of understanding Valeant; let me say right away as categorically as I possibly can that the $99M claimed by Valeant is a lie.

It really doesn’t matter what kind of accounting gymnastics one engages in to try and reconcile them, Sanitas simply did not generate $99M in cash between Q3 2011 and Q3 2012.

Over those 5 quarters, Sanitas had sales of $155M and COGS were $60M. Which means that before any other expenses were even paid, gross profit alone was already below $99M, how in the world could they have generated that much in CASH?

The answer could potentially be that they disposed of some assets and the cash came from there, except that cash flow from investing activities was a negative $3M in total, mostly from CAPEX spending and no cash inflow from selling assets to speak of.

The answer could potentially be that they disposed of some assets and the cash came from there, except that cash flow from investing activities was a negative $3M in total, mostly from CAPEX spending and no cash inflow from selling assets to speak of.

If you want my opinion on why they felt like they could justify to themselves telling their investors that Sanitas generated $99M in cash, here it is:

The only cash inflow that is big enough to even come close to bridging the gap between $15M and $99M is the debt they raised under Sanitas over those 5 quarters.

This is pretty incredible if you ask me because if this is what they call generating cash in order to compute a cash payback analysis, then why not go ahead and borrow the full amount they paid for the company ($450M) on day 1 and say that they paid themselves back in a record 24 hours? I reckon that would be even more amazing.

And if you think that’s bad, then you should know that even for the debt issued number above to make sense in justifying the $99M they’re telling us, they would also have to conveniently pretend that they didn’t use most of the money they borrowed to repay some of the debt Sanitas already had:

As far as pure operating cash flows, we would need to go all the way back to Q1 2009 and add them all through Q3 2012 to get to a total that would be in the $100M range:

And yet we have Valeant telling their shareholders that they did it in the first few quarters after acquiring Sanitas.

So what exactly do we make of this?

I think now is as good a time as any to introduce a conversation that we are unavoidably meant to have sooner or later because you can't bring up Valeant in any discussion without it coming up.

You see, since publishing the first installment of this series of Valeant write-ups last week, I’ve received an incredible amount of messages from people from all over the world. Many of those were congratulating me on my work, warm thanks to all of them. Some were inevitably a bit angry and were calling me names and I even received a handful of threats, no thanks to those.

However, surprisingly (or maybe not) the vast majority of those who wrote had one version of the following question to ask:

“So, what do you think AZ? Is this thing a fraud? Are they crooks or just bending the truth to the limit?”

You see, since publishing the first installment of this series of Valeant write-ups last week, I’ve received an incredible amount of messages from people from all over the world. Many of those were congratulating me on my work, warm thanks to all of them. Some were inevitably a bit angry and were calling me names and I even received a handful of threats, no thanks to those.

However, surprisingly (or maybe not) the vast majority of those who wrote had one version of the following question to ask:

“So, what do you think AZ? Is this thing a fraud? Are they crooks or just bending the truth to the limit?”

Let me first say that for this to be the most recurring question is somewhat sad because I wish investors everywhere would learn that by the time this becomes the main issue, it means that it really should not be a stock that you are investing your savings in. You should just pass.

As far as what I think about those questions, whether something is a fraud or not is complicated because the technical meaning we usually attach to that is that a company is cooking the books.

And to be totally frank about this Sanitas $99M made up number, I honestly don’t think that Valeant went ahead and booked that $99M as cash flow generated by Sanitas’ operations, of course I could be wrong, but I don’t think they did.

What I think is going on, in this particular instance, is just that Valeant makes such ridiculous claims that are impossible to live up to that they've essentially painted themselves into a corner and have no other choice than pull this kind of stuff because the story they've told, and continue to tell, is essentially all that keeps this whole thing going and their stock price heading north.

Just think for a second about what that table is supposed to be providing proof for .

It’s supposed to be showing us how one of the cornerstone of their Deal Model story is being met, i.e. the fact that they achieve very short, 5 to 6 years, cash payback periods on the deals they do.

But that’s not really what’s going on with Sanitas at all, is it?

They paid $450M for it and I’m sure they spent many millions on top of that on restructuring and integration costs, so if we were to assume a total cost of $500M, give or take a few millions here or there, then compare that to the fact that Sanitas generated about $10M in cash flows in the first year under Valeant (Q3 2011 thru Q2 2012), we’d see that they were on pace for a 50 year payback period, a far cry from the 5 or 6 they’re always claiming.

There is no way they would ever show that. That would immediately kill their narrative because everybody knows that Valeant always makes their numbers, they actually somehow always magically beat them.

So they resort to what I just showed you, which is find a way to lie about it.

So I will say this about what this Sanitas cash generated episode means to me personally; even though we might not know for a fact whether this proves that anyone is a crook or not, when someone is willing to go this far to mislead investors, they certainly have the stuff that crooks are made of.

We will leave this particular topic for now and revisit it later in a section that I’ll dedicate to cockroaches but before we carry on with our analysis I would like to leave you with two of my favorite Warren Buffett quotes on this topic for everybody to ponder:

But that’s not really what’s going on with Sanitas at all, is it?

They paid $450M for it and I’m sure they spent many millions on top of that on restructuring and integration costs, so if we were to assume a total cost of $500M, give or take a few millions here or there, then compare that to the fact that Sanitas generated about $10M in cash flows in the first year under Valeant (Q3 2011 thru Q2 2012), we’d see that they were on pace for a 50 year payback period, a far cry from the 5 or 6 they’re always claiming.

There is no way they would ever show that. That would immediately kill their narrative because everybody knows that Valeant always makes their numbers, they actually somehow always magically beat them.

So they resort to what I just showed you, which is find a way to lie about it.

So I will say this about what this Sanitas cash generated episode means to me personally; even though we might not know for a fact whether this proves that anyone is a crook or not, when someone is willing to go this far to mislead investors, they certainly have the stuff that crooks are made of.

We will leave this particular topic for now and revisit it later in a section that I’ll dedicate to cockroaches but before we carry on with our analysis I would like to leave you with two of my favorite Warren Buffett quotes on this topic for everybody to ponder:

"When managements take the low road in aspects that are visible, it is likely they are following a similar path behind the scenes. There is seldom just one cockroach in the kitchen."

“Managers that always promise to ‘make the numbers’ will at some point be tempted to ‘make up’ the numbers.”

Alright, let’s put Sanitas aside for a minute and just concern ourselves with that cash payback table itself.

Let me bring it back:

To tell you the truth, things like Sanitas, and especially the Sanitas financials that we were able to get our hands on, are what I would call perks. They’re perks that we periodically pick up here and there by simply being careful about how we do our due diligence.

But in reality, all an analyst really needed to cast doubt over Valeant’s claims was this table just as it is presented to us for the simple reason that for the very first time they gave us actual cash flow numbers that aren't being substituted by a check mark. Which means that we can finally test them to see if they’re reasonable or not. Simple common sense tests will often tell you all you need to know about a particular situation.

The numbers we're given here are particularly helpful because not only are they cash flow numbers for each acquisition,but they are also cumulative and we know over what time period since they all start with acquisition date and end with 9/30/2012.

This makes our life much easier because the first obvious test to run is to compare them to cash flows generated by the whole company over the same period.

Let’s pick a series of acquisitions to use as a first example.

Say the Afexa, Ortho, Dermik and Inova deals. All four of them were completed between October 2011 and December 2011. So one can add up all the cash they supposedly generated and compare that number with how much CFFO the entire Valeant organization generated between Q4 2011 and Q3 2012 and see if the numbers make sense.

On the left we have our 4 acquisitions and we’re told that they generated $324M in cash from the date each deal closed through 9/30/2012.

On the right we have cash flow from operations for the entire Valeant organization for Q4 2011 through 9/30/2012.

A few more facts to be aware of: In that list on the left, we don’t have Valeant’s biggest money makers that were part of the Valeant/Biovail legacy assets like Wellbutrin, Zovirax, Xenazine, Acanya, Cerave etc. or other major assets like Elidel. Many of these are still among the top 20 products that Valeant has to this very day.

And yet we’re led to believe that these 4 acquisitions alone (that’s 4 out of dozens other acquisitions) generated $324M in cash while the entire Valeant organization had CFFO of $778M over the same period. That’s 42% of the total. I personally have a hard time believing that.

And yet we’re led to believe that these 4 acquisitions alone (that’s 4 out of dozens other acquisitions) generated $324M in cash while the entire Valeant organization had CFFO of $778M over the same period. That’s 42% of the total. I personally have a hard time believing that.

The picture I just presented to you is actually a bit skewed by me including Q4 2011 Valeant CFFO in my comparison because those 4 acquisitions were all done towards the end of the quarter/year and didn’t generate much in terms of cash in Q4 2011.

Here is the revenue each one of those 4 deals generated in 2011 taken from Valeant’s 10-K:

Again, these are revenue numbers, not cash flow numbers, and they’re minimal so there couldn’t be much cash generated in Q4 2011. So a better comparison would be to compare the numbers Valeant tells us in that table with the first 3 quarters of 2012 for VRX cash flows:

- Dermik: $7.6M

- Ortho: $9.6M

- Afexa: $12.6M.

- For iNova, no revenue is given, again from the 10-K, “The revenues of iNova for the period from the acquisition date to December 31, 2011 were not material and net loss was $5 million”

Now the picture gets even harder to believe because the cash generated by our 4 acquisitions would somehow account for 55% of the entire company’s cash flow from operations. Again, color me skeptical.

We can run this test many more times by picking a different series of acquisitions and comparing the cash we’re told they generated to the cash flows from the entire company over the same period.

This was just step 1 in our common sense test. Step 2 is where it goes from doubtful to frankly unbelievable.

Step 2 involves me adding all of them up. That is, all the cash generated from the 11 deals we're given in that table and comparing that total to CFFO for the entire company from the first deal up to 9/30/2012.

The two 2008 deals (Coria and Dow) were done in October and December, so we’ll use as our test period cash flow from operations generated by Valeant starting with the full calendar year 2009 through 9/30/2012.

(Note: I had to use Valeant stand-alone cash flows for the periods before they merged with Biovail in Q3 2010)

This is where it all stops making any sense to me. Somehow we’re supposed to believe that those 11 acquisitions generated more cash than the whole company generated in cash flow from operations.

And not only more cash, but $1 billion more.

To be totally frank with you, I didn’t spend much time at all trying to reconcile that $1 billion difference like I did above for Sanitas for two simple reason:

First, I didn’t have the same visibility because I was not in possession of audited financials for those other deals like I did with Sanitas.

And secondly, I quite frankly didn’t care enough to try and bridge a $1 billion difference; it made zero sense to me on its face how those acquisitions could generate $1 billion more in cash than the entire company did. But then again, we were led to believe earlier that $15M was really $99M, weren’t we?

In any case, as we just saw, this one slide was very helpful and quite telling but unfortunately it was also very short lived. In sticking with Valeant’s Modus Operandi, that table quickly disappeared after making its first and only apparition in Q3 2012 and was never seen again.

The following year, in Q2 2013, Valeant went back to showing the table below as sole proof of how much cash flows their acquisitions are generating:

DoTheValeant is now back, i.e. we're ahead of our Deal Model because we say so and because it is written right there.

As a side note, the constant changing of disclosures and presentations by Valeant is actually one thing that I hope someone will explain to me one day. I've personally never seen anything quite like it.

The way I imagine it happening is that there is a legal clerk in their corporate counsel’s office who is in charge of sending out memos reminding everybody that misleading investors is not advisable and they should do away with this one PowerPoint slide or that one table on another slide etc. If that person really exists, I reckon he or she must be really busy.

Like I told you, that cash payback table went away after its very brief apparition in 2012 and we went years without anything with numbers that we can use for our analysis but being patient eventually pays off because if one waited long enough, then a version that slide made its way back into their quarterly presentation. However, you had to wait until their latest quarterly earnings conference call, that is the Q2 2015 earnings release call, and then pay close attention not to miss it because God knows how long it'll be around this time.

This is the one I'm talking about:

Now, with this one they made sure to not explicitly give us cash flow numbers like they did back in 2012, but it’s just as if they had provided them, isn't it folks?

Because if, for instance, you tell me that OraPharma cost you $312M and that you've generated enough cumulative cash for a 40% payback to date then that means that cumulative cash generated equals $124.8M (312 *40%).

So I can very quickly reconstruct the 2012 table that we've been missing all these years.

And of course by now we know what our next step is:

That $1 billion gap we had before, well it's now a $5.4 billion gap. Pretty amazing.

Similar to the previous difference, I’ll confess right away that I really didn’t spend much time trying to figure out what makes up that difference.

At least for this one, Valeant gives us part of the answer at the bottom of the slide where they say that included in there for Medicis, is cash from the sale of a portfolio of aesthetic drugs in 2014. Fair enough, so about $1.4 billion of that difference should be coming from cash flow from investing activities. We still have roughly $4 billion to go.

I should also be more specific and say that when I say that I didn’t spend time trying to reconcile that difference, what I mean is that I didn’t really sit down to find numbers that would help us close the gap. I can of course think of ways they might be coming up with their numbers.

For instance, Valeant likes to publish adjusted cash flow numbers where they add back a whole bunch of stuff like cash spent on restructuring costs. If that is part of the answer, then someone would have to explain to me how that squares with one of their favorite talking points (this from the quote I shared earlier from Mr. Schiller):

“And lastly, there's been a lot of questions about how we think about acquisition and restructuring costs. They are squarely in the model, which we think of them as additional purchase price. So, if we pay $100 for a business and it costs $10 to restructure it, the purchase price is $110. We need to get a return on $110 in order to justify that investment.”

So they can't be saying that and then adding back restructuring costs to compute payback periods, can they? Especially since none of the numbers under the "Purchase Price" column in the table above includes any restructuring cost. Those are the amounts they paid for those acquisitions.

They are also very fond of showing measures like EBITA. If that's the case I would also need someone to explain the rationale to me for this one because it makes no sense.

The amortization expense addback part of EBITA, I'm not very comfortable with in general as a performance measure because it's assuming that they don't have to spend anything to maintain/replace any of those assets as we'll see in our next installment but, in any case, we take care of that by using cash flow from operations for comparison because CFFO adds back all amortization as well as depreciation expenses.

However, why would you look at a measure that adds back interest expense when assessing the performance of acquisitions that were almost entirely made using borrowed money? We’re talking about a company that had roughly $1 billion in interest expense alone on an $8 billion revenue base in 2014, and that is set to increase this year with the fresh round of borrowing that took place in the first 6 months of the year.

And at the end of the day, I just take them at their word. If a company is telling us that they’re showing cash generated to compute a cash payback analysis, then we should assume that they’re talking about actual cash. Real cash generated by those operations they acquired. Not cash that excludes some of their biggest cash expenses that they get to cherry pick. And if that's the case then that difference is very hard to understand.

And at the end of the day, I just take them at their word. If a company is telling us that they’re showing cash generated to compute a cash payback analysis, then we should assume that they’re talking about actual cash. Real cash generated by those operations they acquired. Not cash that excludes some of their biggest cash expenses that they get to cherry pick. And if that's the case then that difference is very hard to understand.

Alright, let's now put away all those Valeant presentations because they frankly raise more questions than they help us answer, and some of them raise troubling questions like we saw.

We'll focus our attention back on the central point of this whole post, IRRs and what I've dubbed the IRR Fallacy.

The reason why I said at the very beginning that this fallacy was by far the one that puzzled me the most is because it's one that is easy to verify or test in my opinion.

IRR is nothing more than a discount rate that gives you a present value of zero for a stream of cash flows and if we know the initial outlay of cash, which we do for all those acquisitions, then we can get a pretty good idea of what future cash flows need to look like for a 20% IRR to be achieved. Excel does all the work for us. After that, all one has to do is analyze Valeant's actual cash flows and see if they match.

I personally like any analysis that involves studying cash flows because the cash flow statement is by far my favorite financial statement.

We’ll see when we discuss Cash Earnings in Part V how technical it can get when trying to understand what to make of expenses that are capitalized vs expensed when looking at the income statement and the balance sheet. In some industries where revenues and expenses have to be estimated because they depend on contracts spanning many years or even decades, the numbers on the income statement will depend as much on who is computing them as accounting rules in place.

However, there is a certain soothing simplicity to the cash flow statement in that, at the very bottom, all the inflows and outflows of cash have to reconcile to the cash you have in the bank. So, it's really hard to fake cash flows. When you tell people that you are generating a certain amount in cash then that amount better be found somewhere on that statement.

However, there is a certain soothing simplicity to the cash flow statement in that, at the very bottom, all the inflows and outflows of cash have to reconcile to the cash you have in the bank. So, it's really hard to fake cash flows. When you tell people that you are generating a certain amount in cash then that amount better be found somewhere on that statement.

Let's go over a few IRR examples:

Let's use Bausch+Lomb first. B+L was acquired in late 2013 for $8.7B and Valeant's estimate for restructuring costs is $600M (This is the estimate given in their 2014 10-K). So a total cost of about $9.3B.

Here's a very rough picture of what cash flows would need to look like for this deal to achieve an IRR of 20% or more over a decade (2014 through 2023):

The first issue with this picture is easy to spot, the total CFFO for the whole company was about $2B in 2014, so I would think that B+L, which is only a fraction of Valeant, would probably have a hard time achieving these numbers.

I should also preempt something that I know will happen for sure, which is that people will email me arguing that the picture I'm painting is misleading because cash flows might not start that high but Valeant will grow B+L, hence grow those cash flows over time. And that's fine, all I'm trying to do is just show folks very roughly what it takes to achieve a 20%+ IRR.

Anybody can play with these numbers as much as they want and build many scenarios.

If for instance we assume that in 2014 half of Valeant's cash flows came from B+L (even though B+L is less than 1/2 of total VRX revenue), so about $1 billion, and also assume that they will grow those cash flows at a 20% CAGR for a decade - a very aggressive and unrealistic assumption in my opinion but we'll just go with it.

Then, the IRR picture would look like like this:

On the left we have our original scenario and I added the one on the right with a beginning $1 billion in cash flows compounded at 20% for a decade. and even though the new scenario produces about $3 billion more in cumulative cash flows over those 10 years (~$26B vs $23B) the IRR drops.

Of course I'm not really showing anything new here, we all know that this is how time value of money and discounting works. The further out you push those cash flows, the more you will need them to be really really big to achieve a 20% IRR.

So I'm not really looking to quibble about exact details, everybody should decide what set of assumptions they want to use and then see how it affects the IRR picture. My goal is to simply make sure that people see and understand what a 20 or 30% IRR entails, because it's quite an incredible claim to make.

Let's say I wanted to reconstruct what Valeant's Deal Model looks like for the $16 billion Salix acquisition and see what assumptions I would need to build into the model.

Here is the first and most important fact to keep in mind as we work through our assumptions:

- Salix had about $1.1 billion in sales in 2014.

Now, what about cash flows? Well, I'll use as my starting point Valeant's own number. An "Adjusted Pro Forma EBITDA" (quite a mouthful) number for Salix of $850M that they've shared with investors in many SEC filings like this Prospectus. The way they came up with $850M is by compiling estimates. First, Salix' own adjusted EBITDA estimate of $350M and then adding on top that their own estimate of synergies to be achieved with the acquisition, $500M.

But I have to make my own 3 adjustments to that number:

- Since Valeant says that they always overachieve on synergies I will bump that $850M number up to $1 billion

- To take into account many other upsides to the deal that will surely come with it like new indications approved for some drugs and generally speaking because Valeant is so good at acquiring companies, I'll double that number to $2 billion.

- And finally, we need growth, so I'll compound that $2 billion at a 20% clip over a decade.

I want to take a moment and remind everybody that this a company that had $1 billion in revenue last year and I'm starting my model with them delivering $2 billion in cash flows in year 1 and then growing that for a decade at 20%.

Folks, I know all of this is plain silly, but you see, I really had no choice but to engage in those acrobatics, in order for me to achieve a 20% IRR on a $16 billion investment:

Now, let me ask everybody something, is this what their Deal Model looks like? And if not, what exactly does it look like then?

I started by showing you the math for Valeant's biggest acquisitions, Salix and B+L, because there's a new talking point that has surfaced lately where they imply that on the really big acquisitions, the 20%+ IRR and 5-6 years cash payback periods talking points don't necessarily apply. They just achieve adequate returns on those.

Fair enough. However I would have to point out that, there's a bit of revisionism going on then because this is what they were saying when they acquired B+L:

See slide 4 of this presentation given when they announced the deal: B+L Acquisition Conference Call

And here's Mr. Pearson's comment on that slide taken from the conference call transcript:

"Turning to Bausch + Lomb itself. With pro forma revenue of both companies of over $8 billion and expected synergies of at least $800 million captured by the end of 2014, we have been able to make our financial criteria of 20% plus IRR, our first criteria for any deals."

So it sure looked like they weren't afraid to claim at the time of the deal that, in Mr. Pearson's own words, "they had been able to make their financial criteria of 20%+ IRR".

Of course I can understand why the story is gradually shifting because reality has a nasty habit of being quite different from the overly optimistic predictions managers like to make.

So if not the big deals, then the smaller ones should be delivering 20%+ IRRs.

The ones that were public companies before being acquired by Valeant are the easiest ones for us to run our common sense test on because they had published figures.

Let's take Obagi for instance. Valeant paid $437M for Obagi. So our rough picture of what 20% IRR cash flows over a decade would look like this:

Here's the issue I have with this picture. Valeant acquired Obagi in April 2013 and the previous year, calendar year 2012, Obagi had sales of $120M. Here's their last filed 10-K: Obagi CYE 12-31-12 10-K.

Maybe it's just me but I have a hard time believing that a company that had $120M in sales can just start producing $105M in cash flows just like that.

Of course by now we know of a another deal that will have a hard time achieving that IRR goal, Sanitas. Sanitas was acquired for $450M, and we know from their financials that they delivered about $10M in CFFO in the first year under Valeant. So here's what cash flows would need to look like from year 2 - 10 for that 20% IRR to materialize:

Color me skeptical on this one as well. Sanitas had $130M in sales during the first 4 quarters after being acquired by Valeant. Good luck coming up with $135M in cash flows.

To tell you the truth, the one thing that makes it really hard for me to understand the kind of momentum that these IRR claims have gathered over the years is that Valeant shareholders have the ultimate tool at their disposal to prove or disprove them: Valeant's own cash flows.

Since we know how much Valeant paid for all those acquisitions, we can map out a rough idea of how much every single one of them needs to bring in to get to 20% IRR like we did for the few examples above. Then all one needs to do is add up those cash flows for any given year and compare that to Valeant's cash flows. Now, I haven't done this math myself but I'm willing to go out on a limb and predict that if you do that, they will be off. And by quite a margin.

Alright, I think everybody by now knows where I stand on these 20% IRR claims. So I'll just stop here and conclude our discussion today with a little editorial commentary to share my final thoughts.

You see folks, I simply don't believe that it is given to man to be able to go out and do hundreds of M&A deals and have each one of them generate IRRs of 20% - 30% like Valeant claims. The one ingredient that would be required to achieve that is not some mysterious Deal Model, that ingredient is magic, which I shouldn't put beyond Valeant at this point I guess.

And the reason why I do not believe it to be possible is because the world simply doesn't work that way. It really doesn't.

To be clear, I am not saying that a person can’t generate those types of returns. I’ll even admit that the goals I set for myself in investing are high numbers like those. But the thing is that individuals like me have the advantage that we spend time turning over rocks and looking for dislocations between price and value in capital markets that would allow us to pick up undervalued securities. And I firmly believe that if someone is diligent and patient enough, he or she can achieve great returns.

However, try to imagine what would happen to those returns if whenever we find something interesting, instead of simply buying the undervalued stock, we had to instead go and negotiate the sale of the entire company with every set of shareholders and management teams. The answer is that those returns would very quickly go down and by a lot. And the kicker here is that we wouldn't do it just once or twice, but dozens if not hundreds of times, and still generate 20 - 30% IRRs every single time.

The odds of that happening are probably as low as me, a non-British male, being chosen to be the next Queen of England.

And the reason for that is simple. The world is not set up in such a way that people willingly hand you things for free. There aren't hundreds of companies and assets just laying around waiting for Valeant to come pick them up and achieve eye popping returns all the time like they claim.

This whole IRR story is just that, a story. And quite frankly to believe a story like this, in my opinion, requires the type of suspension of disbelief that is needed when we go watch a James Cameron movie. And yet people buy it. A lot of people buy it. It’s incredible.

I’ll tell you one thing that all of this has done for me however; it has taught me how potent the combination of a good story that is well told and a rising stock price can be on the human psyche. I am confident that if you took away the Valeant name and presented the same story to most Valeant investors about some random company whose stock isn't doubling every year but still claiming that they achieve 20-30% IRRs on hundreds of deals, their first reflex would be to check if the person giving the presentation is not Bernard Madoff. At the very least, I know that they would ask to be shown numbers to verify if it's true. And here for me is where the biggest issue lies.

Because there is a very easy way to handle all of this, even easier than doing all the math we went through together, though I certainly encourage every shareholder to always do it.

Instead of believing everything Valeant says in their presentations or getting mad at that one guy that goes by AZ Value on the internet and sending him emails yelling at him like some folks have been doing; Wouldn't it be better for Valeant shareholders to simply email their IR department and ask them to provide numbers with their claims instead of tables with check marks? Then we can put all of this to rest for good, and I promise you that if proven wrong, I will publish another piece and officially stand corrected. Until then, I have a feeling that they will be content with simply #DoingTheValeant and their shareholders will continue to run the risk of waking up to a very nasty surprise one day.

Alright folks, that's all for today. Please join us next time when we'll go over Cash Earnings and valuation, I promise not to make you wait this long this time.

As always, please be careful everybody and I bid you all good investing.

AZ Value